I am so excited that two of my favorite poems have been published in Deaf Lit Extravaganza, another anthology put together by the wonderful John Lee Clark, author of Suddenly Slow and Deaf American Poetry: An Anthology.

If you are at all curious about the Deaf community, I urge you to pick this up. It had great range, from fiction to poetry to non-fiction, and features some very talented writers.

From the introduction by John Lee Clark:

“…this book represents the latest blow to the audist vision of deafness as a calamity, as something that must be fixed at all costs.”

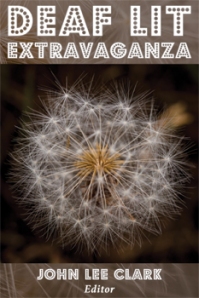

The cover of the book, a dandelion, is a tribute to Clayton Valli, a ASL poet and linguist. His famous ASL poem “A Dandelion”, which is about the persistence of ASL despite oralists attempts to weed it out, is transcribed in the book, though I love the ASL version below:

[A note from Wikipedia:

“Audism is the notion that one is superior based upon one’s ability to hear, or that life without hearing is futile and miserable, or an attitude based on pathological thinking which results in a negative stigma toward anyone who does not hear.”]

Pre-ordered our copy today!

LikeLike